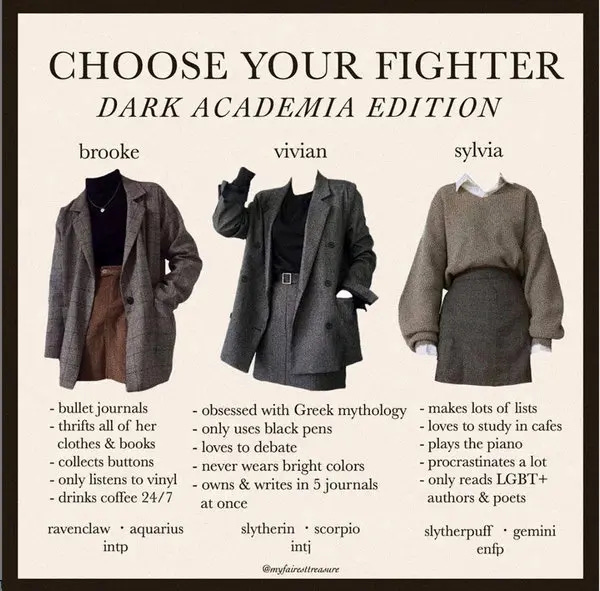

I was at a conference recently—giving a talk on aesthetics as a matter of fact—and got a few comments from the art historians about how “very dark academia” my look was. I felt a bit caught out. I don’t think there’s nothing to that felt-accusation: I have a tweedy look, wear a lot of neutral tones that realize themselves in ties, sweaters, dress shirts, blazers, and long, librarian-ish skirts. Where it’s more colorful it still follows the same general form, or indulges in something romantic and old fashioned (billowy, patterned sleeves, and so on). And generally, I love being overdressed.

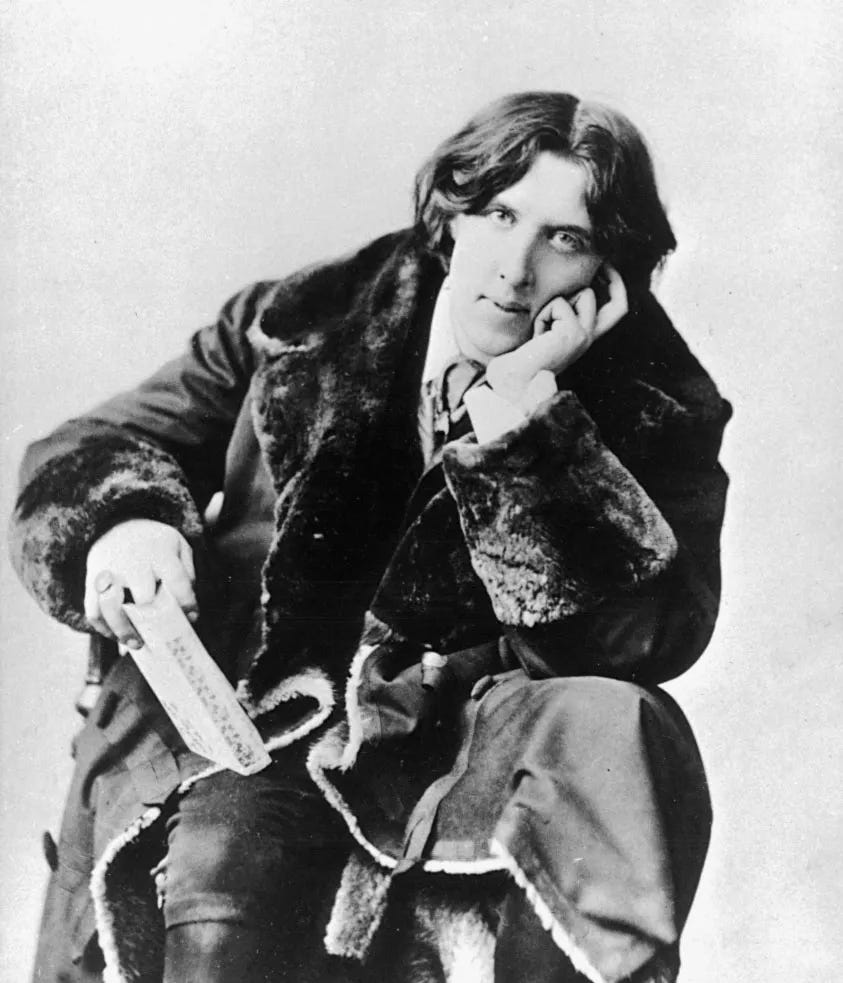

It’s not so much that I am self-consciously modeling myself on the online aesthetic. In fact, I lack of lot of the same cultural touchstones. I’ve read only a single Donna Tartt novel and thought it was just okay (though I really wanted to like it). Sylvia Plath remains unread. Harry Potter is safely confined to my childhood. Greek statues and classical poetry don’t speak to me; my preferences for painting, novels and poetry are generally aggressively modernist. Oscar Wilde has admittedly won a fan in me, at least insofar as I’m rather enthusiastic about the Decadents and other artists who were transformed by the revolution in aesthetics in the last decades of the 18th Century and beginning decades of the 19th. Apparently Virginia Woolf makes the list too and Mrs. Dalloway was much loved on the recommendation of a friend. I could flatter myself and say that this is just convergent evolution or that I had somehow taken lead of the look, but the first encounters with it resonated with me, and felt like a natural direction of departure from how I was already dressing. The whole affect spoke to me.

A lot of the discussion of dark academia takes place from the vantage of a kind of detached, almost anthropological perspective—as though, even for defenders, there is something a bit embarrassing about dark academia or being labelled with dark academia. The intro I’ve typed out here carries unmistakable traces of that embarrassment. Part of the social danger of identifying with dark academia, I take it, is in identifying yourself with something that essentially emerged out of youth culture and which finds its primary proponents and enthusiasts in young women. But these are platitudes—not entirely without truth—that we always trot out when something we like is under attack. I think there are a couple of deeper explanations. In a sense, the subculture can’t endorse itself without qualifying itself. It endorses values that are, ironically, anti-subcultural and clash with the nascent political consciousness of the youth-skewed audience. At the same time, it is exactly those clashing values that make dark academia so seductive. It is, after all, a genre fixated on dark revelations, a sense of otherness and being out of step with your time.

The End of Fashion

I want to start on that last point, that the look fundamentally involves a sense of being out of your time. Many of the looks that we see today are inspired by past eras and past subcultures. “Goth” still commands a look, but much less of presence as a musical moment or genuine subculture. We recycle styles from the 70s and the 80s every so often, letting them go out and then back in. It’s no surprise that every zoomer has the mustache of their millennial coworker’s dad. I want to suggest that dark academia is just a small part of a wider cultural trend of looking to the past for materials that we can fashion ourselves from. But what does this trend say about us? Here’s a somewhat speculative answer:

“Idealist history”—or what might be more accurately called Hegelian philosophy of history—has long been on the retreat. It seems less and less like the spirit of history is going anywhere. Concepts are not out there in the world clarifying themselves through historical processes until they reveal their inner essence, freedom or something else similarly inspiring and optimistic. Many modernists thought of their project fundamentally in terms of trying to reveal the telos or the authentic inner essence of art, especially as something that could be worked out in terms internal to the medium. In other words, modernist painters thought they could reveal the nature of painting by doing painting. Modernist musicians thought they could get at pure or absolute music simply by working within the medium of music. But this paradigm collapsed by the time the 70s rolled around. This, at least, is the story that Arthur Danto gives us.

It seemed impossible at this point to look at a shared canon and try to figure out where to go from there. There was no more shared canon or even a sense that one was competing to build a new canon. Danto puts it cheerily:

But in an immeasurably more modest but similar way, the claim that art history is at an end couldhave been the end of art history-a declaration of artistic freedom, and hence the impossibility of any further large narrative. If everyone goes off in different directions, there is no longer a direction toward which a narrative can point. It is a wholesale case of living happily ever after.1

Like all concepts that undergo this marvelous process of historical clarification in Hegel, it turns out that freedom lies atop, waiting to be seen from the vantage of philosophical consciousness.

Danto’s primary examples here are in painting: Greenberg’s self-avowed Hegelianism makes a nice foil for Danto’s own while slotting neatly into his story. But it’s not difficult to imagine similar kinds of stories in other artforms. The monomaniacal pursuit of absolute music seems more or less dead. Instead leading composers head off in different directions, hanging onto whatever historical or intercultural ideas catch their interest. John Cage experiments with silence by incorporating ideas from a mish mash of east and south asian philosophers. Arvo Pärt gives us a heady mixture of medievalism and minimalism. Lera Auerbach gives us experiments that combine romanticism with crashing, dissonant clusters of chords. It is difficult to discern a definitive direction for history to take in all of these trends, and these are just developments that fall under the vague label of “contemporary classical music.” Each genre has a similarly diffusion of interests and developments, constantly churning out new sub-genres and trends. Rap and electronic music seem particularly explosive with new directions and ideas at the moment.

What these examples are supposed to show is that artists across various media are becoming interested in working from their own personal canons. They become preoccupied with their own luminaries and own micro-trajectories, trying to work out the ideas of a subgenre or a handful of eccentrics rather than the idea of art writ large.

The idea that a similar process happened in fashion history doesn’t seem like a terrible stretch, in large part because dress has often come attached to other cultural affiliations. As we divided more into subcultures (perhaps as a result of the end of art), there became less of a sense that the culture was collectively doing something with fashion or that the history of our clothing was going somewhere. And as subcultures become interested in what was happening with a particular historical moment, the clothing comes to reflect that. We all come to look a bit old fashioned—or at least carry a bit of old-fashionedness with a new coat of paint—but in different ways. Even “mainstream” fashion, if there can still be called such a thing (maybe “normie” is just another subculture now) takes some inspiration from the past. Many of us have seen the posts complaining about how all of the new dresses that were in last summer were a little too “Little House on the Prairie” for their tastes.

My sense is that dark academia came from just the same process that revitalized the goth or punk looks, or what brought them into being to start with. There was a cultural milieu forming around a certain kind of art (in the cases of goth and punk, music especially) and a look showed up to reflect it. The look that showed up just so happened, in this case, to involve a lot of tweed. Why? Because the milieu was forming around classic literature and works inspired by classic literature. These books are associated with academia, so it’s natural to turn there for fashion inspirations. Then teen and early-20s angst demands that you add a little edge to it, hence the “dark” in “dark academia.”

Refuge From Poptimism

People often tag the dark academia look as a bit Harry Potter inspired, and while I think that might be true in some cases, I think dark academia may have been in part a reaction against poptimism. I use “poptimism” loosely here: the proper noun Poptimism refers to a particular debate in music criticism between enthusiasts of pop and rock music enthusiasts. Somewhere along the line it’s just been imported into a helpful portmanteau of “pop” (as in “popular”) and “optimism.” One expression of this was in an explosion of interest in genre fiction and a spirited defense of the merits of popular fiction against the “elitist” (both imagined and actual) attitudes of genre fiction readers. Another was in the 2010s defense of comic book movies, like Marvel and DC movies against what nerd culture fans called boring and pretentious and always “foreign” (but not problematically so, we promise) cinema.

You’ll notice that the defense at some point becomes an offensive. It’s not just that the hottest fantasy novel out right now is just as worthy of critical and academic consideration as a Jane Eyre or a Wuthering Heights, it’s that you’re stupid and pretentious for even liking these old timey novels. You just hate fun, and would be having so much more fun if you just got with the times. At least, this is the social media environment that has felt very alive to me in my teens and to a certain extent in my 20s. This is the kind of environment that you come of age in when you have one foot in the door of the subculture that likes video games, fantasy and science fiction.

If you really like these old-fashioned novels or really anything that takes the same kind of flak from the poptimist crowd, it ends up getting pretty grating and you are going to start seeking out other people to both hang out with and talk about your interests and join your righteous cause in the culture war.

When enough people are alienated and disaffected in the right ways, they tend to come together to form micro-communities. This becomes easy in the world of social media. I think this is especially true of Tumblr, where a lot of the influential “aesthetic” cultures we’re familiar with today trace their roots. It’s anonymous, giving users the freedom to say much more than they would be comfortable sharing under their real name, but also very directed on users rather than pre-existing interest groups. But it also allows tags to form for people to search after content.

As a result popular personalities can draw groups of similarly minded people and give certain subcultures more cache by tagging their posts with it as it comes more solidly into being. Moreover, users more or less spontanteously form communities when their posts frequent a lot of the same tags.2 People who are really into Anna Karenina don’t need to look for a pre-existing subreddit: they can just tag their posts with it and hope likeminded people flock to it.

I think it’s easy for people who were interested in the core building blocks of the subculture to find each other in this eco-system. Probably one of the most iconic features of the early subculture—one that almost certainly that drove these spontanteous social media communities as a cult hit—was Donna Tartt’s novel The Secret History. I haven’t read The Secret History,but I’ve read another Tartt novel, The Gold Finch and there’s a kind of striking moodiness and aestheticism to her work. She’s obsessed with documenting these lists of beautiful things. It’s a bit like the middle chapter of Dorian Gray (another incredibly popular novel among the dark academia crowd) where Wilde lists all of the beautiful things or the novel that chapter acts as an homage to, Huysmans’ Against Nature. Tartt characters (in my reading and in reports on the secret history) are so often moody loners who find solace in beauty. They fundamentally are these kinds of late 18th-to-19th century characters who are obsessed with beauty in the face of a dark and terrible world. They are characters of (at least in the mind of the author and many readers) sophistication and taste. They are obsessed with old, high cultural artifacts that require specialized knowledge or perceptual training to appreciate. The aesthetic ethos is exactly the opposite of the populist-poptimism that was so endemic to the 2010s and that championed wholesome, easy viewing. In this sense it was a kind of comfort reading for people who saw themselves as interested in difficult, acquired tastes.

The Problems of Taste and Authenticity

In the previous section, I suggested that Tartt’s novels may have been an early exemplar of the dark academia subculture. The Secret History in particular was a rallying point that really served to express the values of the subculture in a single novel. One of the core values of dark academia, I think, is taste—even if the fans fail to actually live up to having taste, rather than clinging to the commodified symbols of taste.

Another value that I tend to think is important to the subculture is a kind of raw authenticity. Dorian Gray is another pivotal work for the dark academic subculture and it comes infused with Wilde’s individualist philosophy that placed a kind of idealized self-expression in art as the pinnacle of a life well-lived—a kind of hyper-aesthetic Aristotelianism paired with Romantic individualism. Wilde is constantly worried that genuine and extraordinary people are going to be stifled by the opinions of banal and ordinary people. My sense is really that this infused the subculture with a sense of the importance of self-expression and maintaining an authentic self-expression.

As I said at the start, part of the problem with dark academia is that these values can’t endorse a life that’s too dominated by the dictates of a subculture. Given that dark academia endorses them, it struggles to endorse itself. In more precise terms, taste runs into difficulty when it’s too in line with others in a community: it immediately makes us suspicious that what’s being exercised is actually taste and not mere conformity with a community norm. Moreover, there is a strong trend in aesthetics of thinking of aesthetic taste as something individualizing rather than conformity making.3 Taste seems to be something that we’re supposed to work out for ourselves. The problem is particularly pronounced where the objects of shared obsession are canonical works of art: there’s one hell of an error theory for your taste when everything you love is just whatever the Western canon is. Similarly, it’s difficult to come across as unapologetically authentic when all of your friends are doing the same thing you are. Dark academia in a sense has the same problem that punk continues to have: when the rowdy youths rebel, they all rebel in the same way.

There are, of course, alternative ways of thinking about taste (perhaps authenticity is in a bit more firmly in a bind) that enjoy popularity among working aestheticians. Plenty are willing to give up the Romantic image of the genius spontaneously coming to generate something hitherto unseen, independent of whatever rules came before—all while locked in a state of tortured ecstasy. There are plenty of options available that celebrate the community and socially scaffolded nature of various forms of aesthetic value that they might latch onto. But the serious problem is that the conventions of dark academia as a genre don’t allow it: dark academia is really tied to the idea of the mournful genius; the idea of the special, sensitive person who has to make her own place in a world that doesn’t understand her. And this gets dark academia in the awkward position where it can’t fully endorse its own values and still retain its status as a subculture.

A Lengthy Aside: Alternate Constructions of Queer Identity

The Picture of Dorian Gray, Call Me By Your Name, Mrs. Dalloway, Maurice, Giovanni’s Room—many of the titles that dark academia claims as its own have something in common beyond an obsession with tweed and bookishly handsome men in glasses: an at least passing interest in homosexuality. But the way these works, especially the older, more canonical works, portray homosexuality is somewhat alien to how it’s portrayed in much of contemporary media and in contemporary attempts from within “queer communities” to construct themselves.

The phrase “queer joy” has, by now, a certain buzziness to it. “Joy” more broadly has taken on a kind of mystique or aura in activism-oriented spaces. There’s a strong sense of importance directed at portraying minority communities as joyful to the point that it can almost seem like there is something almost exotic and ethereal about these particular expressions of joy. Similarly, the external expression of gayness has become associated with camp. But it is a specific kind of camp that prizes effusiveness of color, brightness, glitter, and an intoxication with the excesses of bad taste, an almost ravenous desire for ridiculous, plastic-y ornament.

But in Dorian Gray the homosexuality of the protagonist comes with doom in train. Dalloway puts homosexuality into the periphery, something that has to be suppressed but still burns violently and irresistibly in memory. As a matter of fact being queer at the end of the 19th Century or start of the 20th, as Wilde and Woolf respectively were, was an unpleasant experience, liable to make you think something was fundamentally wrong with you. The aestheticism endorsed by Wilde moreover seems historically to have emerged, at least in part, as a result of a thoroughgoing form of philosophical pessimism that struck 19th Century Europe. This position makes the works celebrated by dark academia well suited to those who struggle to embrace joy as part of their self-conception or, more dramatically, reject “joy” as the normative ideal for their lives (or anyone else’s); to those for whom there is a plurality of alternative goods that can be found in the gloomy and brooding.

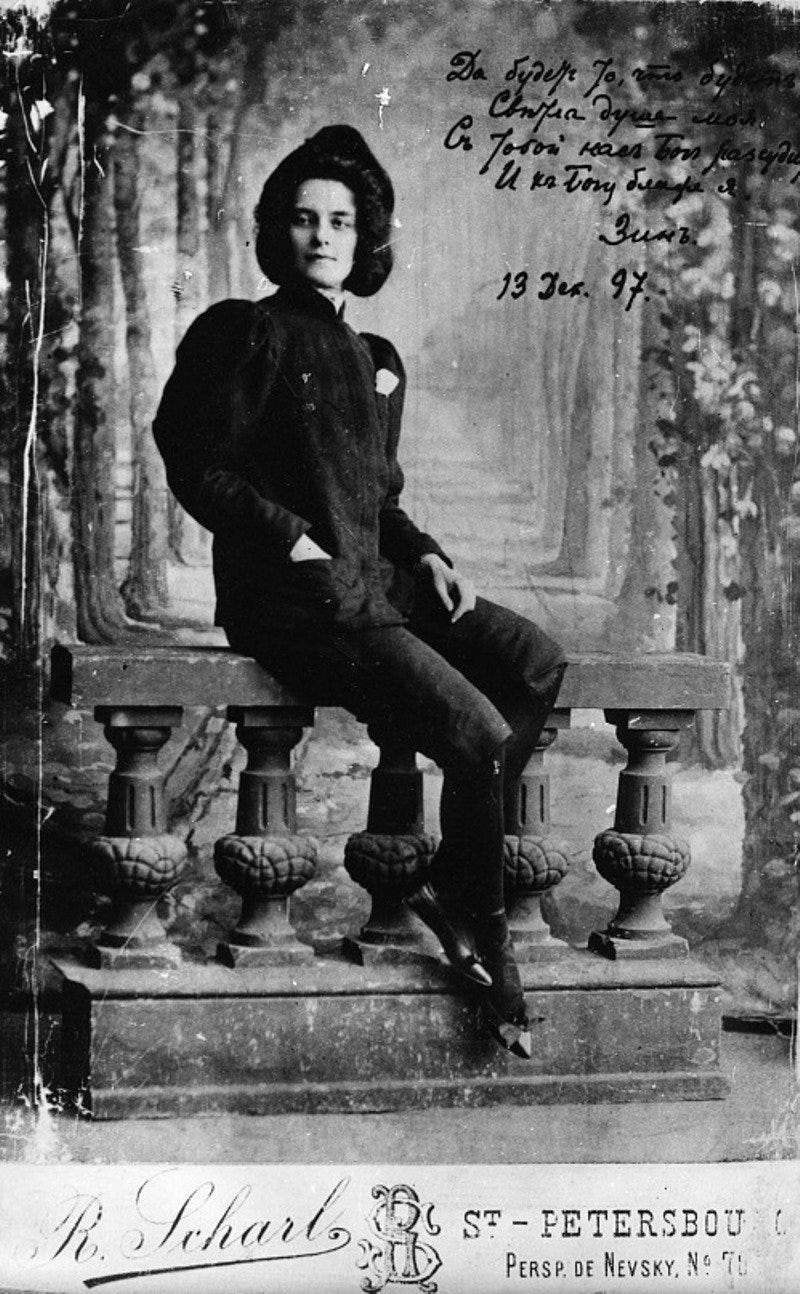

Merely as a result of the intersection between Decadent or Bloomsbury aestheticism and its intersection with covert homosexuality, dark academia can seize on the opportunity to construct an alternative starting place for the construction of one’s own identity, integrating one’s queerness into a cohesive, historically mediated whole without twisting yourself into a monolithic expression of queer joy. I, myself, feel sympathy for this project and I think some of my fixation on Zinaida Hippius4 comes from her heady mixture of gendered experimentation, pessimism, and aesthetic mysticism.

The actual garments—maybe the core component of dark academia—are even conducive to these experiments with alternative queer construction. Most of the articles are androgynous, and the basic outline of the outfit can survive individual parts being swapped out for more explicitly gendered items well. Blazers, sweatervests, turtlenecks, button up shirts—all of these cast in neutral tones are something that anyone can wear without compromising one way or another on their gender identity. This all makes it ideal for transgender and nonbinary people who can sometimes have reason to mitigate some of the abrupt shock of transitioning or be able to play with different forms of gender expression without drawing too much suspicion from those around them.

Dark Academia: Good or Bad?

The view I’ve given so far is a bit checkered. On the plus side it offers an alternative way of conceptualizing queer identity that isn’t catered to by many of the depictions in our current cultural moment, it offers a refuge from poptimism for people who just want to share in a love for classic novels, it fosters values that (I think) are good like the development of ones taste, an appreciation for (at least some forms of) beauty, and the cultivation of oneself as an individual. One the other hand it can lock one in on too narrow a sense of good taste, and create circumstances in which practitioners more often fail to live up to their own personal and aesthetic ideals. But in the end, I still dress the way I do, so there is some level in which I see it as a net positive. Once you’ve integrated a way of presenting yourself into your persona and your way of life, it’s difficult to let go of.

I think there’s yet a moral to the story: if dark academia fans want to be taken seriously—and take themselves seriously—then they have to give more thought toward the project of reconciling taste and personality with membership in a community where people start looking a bit same-samey. But this is the situation that most all of aesthetic subcultures find themselves in. And, as we saw at the start, now is the time of subcultures.

Arthur Danto, “The End of Art: A Defense,” History and Theory 37, no. 4 (1998): 127-43.

My sense is that tagging is a little passe now though—at this point the Tumblr communities are entrenched and more or less know the frequent fliers in their circle. This is my experience, at least.

As I’ll elaborate on in a moment, the opposite trend is present as well.

Also transliterated as Gippius. The family name comes from outside of Russia as Hippius, but in Russian it’s transliterated as Гиппиус. According to Pachmuss’ biography Zinaida Hippius: An Intellectual Profile she was insistent on Hippius. I think Gippius sounds better, but what can you do?