Disco Elysium and Genre

What genre fiction and literary fiction can learn from each other and how Disco Elysium acts as an exemplar for synthesizing the two. And a little bit of gushing.

When people are asked to compile lists of the best-written video games, you’ll usually get a smattering of Obsidian titles like Knights of the Old Republic II: The Sith Lords or Fallout: New Vegas, passing down along the way to older roleplaying games like Planescape: Torment or Vampire: The Masquerade: Bloodlines. And passing somewhere or other along the list you’ll notice another title, Disco Elysium. It feels strange to see it there. The phrase “games writing,” after all, conjures up a familiar set of conventions. You expect competent execution of an interesting, albeit perhaps somewhat formulaic genre fiction plot—you have to go on an epic journey to become a hero and save the universe—with strong character writing, and intriguing world-building, perhaps the guilty addition of a few tropes to be lovingly or hatingly dissected by fans. Sure, Disco Elysium hits a few of these marks (character writing, world-building), but the writers seem interested in a fundamentally different project than “games writing.” One of the key things that makes Disco Elysium so good is how readily its writers see resonances across genres, making each tradition they borrow from work together and harmonize. Following the music metaphor, I sense this point lends itself less to a conventional organizational structure, but more like a musician traveling along different variations, jumping from chord to chord along the circle of fifths.

Let’s start with prose. Prose is the sort of thing that games writing, with its roots firmly entangled in genre fiction, doesn’t tend to go crazy about. Genre fiction often focuses on serviceable prose, rendering it nearly purely instrumental in telling the story. One of the most popular contemporary fantasy writers, for example, frequently talks about writing as a “clear window” into the world1, a claim that tweed-clad readers of Shklovsky would scratch their eggish heads at.2 Genre fiction—by and large—is decidedly not an art that’s obsessed with form. Disco Elysium, however, is. The prose is genuinely first rate in a way that stands up to some of the great novels of the 20th Century—the kinds of things that spill out of the pens and type-writers of a Virginia Woolf, Vladimir Nabokov or an Andrei Bely. And it does so in a way that does not come across as a cheap imitation. They don’t need to steal their pale fire from the sun. Here’s a random line pulled from one of my favorite skills:

SHIVERS - The shop around you feels ancient suddenly, damp and saturated by the coastal air. The books are rotting, a great cold lives here. And there too — 1200 metres away, on the urban coast. The dark shape of a church is reflected on the water.

Much of the game is like this: moody, murky, heavy, carrying you on with a natural sense of rhythm, dragging you to some point you can’t quite recognize, freely mixing precise, numerical measurement with hazy, primordial intuition. It intimates something just beyond the border of perception, trying to make itself intelligible to you.3

The stylistic flourishes most often come out in the Shivers skill—though I struggle think of a feature of the game that isn’t particularly well-written. Shivers is an odd skill. It allows you to stop listening to the people and happenings directly around you, instead attuning you directly to the city. It gives us our first major breach across genres, drawing heavily upon the tradition of the modernist city novel. Much like Bely’s Petersburg casts the titular city as its own character, the Shivers skill casts Revachol as a living, breathing entity that reaches out to you directly. But the city is also presented as more than streets, and particular places. It also takes on the history that these cities result from, becomes imbued with the mythos of the literary culture. Petersburg lingers under the statue of Peter the Great, mounted on horseback, two feet rooted in earth, two feet kicked upward toward the horizon, animated by Pushkin and waiting to take life again. Revachol lingers under the destroyed but reassembled equestrian statue of Filippe III, horse bucking toward the horizon in the same pose, his history waiting to be uncovered. Bely’s Petersburg is the city of Dostoevsky, of Gogol, of aging imperial bureaucracy, of inchoate waves of Westernization, of nationalism, of Greco-Romanism, of mystic revelation. Revachol is, just as well, a city of failed uprisings, of exploitation and by some far away liberal polity, of unrest, of inchoate modernization, of a great and terrible air that hangs over everything. Both wallow in the aftermath of a humiliating defeat. Both intimate their status as a focal point between planes. Both promise the complete remaking of the world; that everything can be undone and reassembled into something unfathomable, incomprehensible at any moment. And while both can be surreal, ethereal, and abstract, they’re both invested in a sense of place, of cities as sedimentary layers of cultural and political accretion, and above all historicization.4

What’s so interesting about the way the city layers culture on top of history on top culture (etc.) is that the world is a distorted mirror of ours. We get uncanny glimpses of ourselves in racist mugs and disposable bottles, computers that run on tapes and radio waves, oceans devouring the earth inch by inch, in a woman from not-quite-the-Netherlands, in revolutionary matronymics, in bestselling, trashy novels, half-baked occultism, saint-stages-of-the-world-spirit, a something-like-NATO, and on and on. It is as though the inner essence of these things survives, but out of step with us, our expectations, the actual practical and cognitive flow of our lives. All of the conceptual and physical material of the world, the ideologies, the people, the places take on a carnivalesque quality, waiting to be played with, entertained, and experimented upon. The jamais vous (to borrow a phrase from the signature Thought Cabinet5) of the whole affair is defamiliarizing—and here we make good on the Shklovsky namedrop: it presents the world back to us as something new and surprising, that can be seized on with new attention. In other words, the science fiction setting plays off of the emphasis on experimentation and form that we find in the city novel. Both present the world in a way that is refashioned, unfamiliar, and disruptive of our usual process of sense-making.

I should emphasize that these parallels are not coincidental. The writers have explicitly cited Estonian poet Arvi Siig as an influence, a modernist similarly interested in depictions of the city and city life. Kurvitz went so far as to say that “Without [Siig’s] modernism, Elysium - the world the game is placed in - would not be half of what it is” in an acceptance speech for an arts award. Much of the genre fiction world (games writing included) spends its time cannibalizing itself for influences, but Disco Elysium is striking in how it draws fresh influences from dramatically different genres. Disco Elysium is certainly not the first modern roleplaying game, but it might very well be the first modernist one.

Of course, once we move out of roleplaying games, we can see that there have been other modernist-inflected experiments in alternate reality science fiction. And just as well there have been modernists who have borrowed from the techniques of science fiction. The Anti-Terra of Nabokov’s Ada, or Ardor comes to mind. We can also probably class Samuel R Delany’s Dahlgren as a thoroughly modernist science fiction novel. But we notice that these overlap projects are rare. While Disco Elysium isn’t exactly sui generis in this respect, it does mark the game out as something unusual.

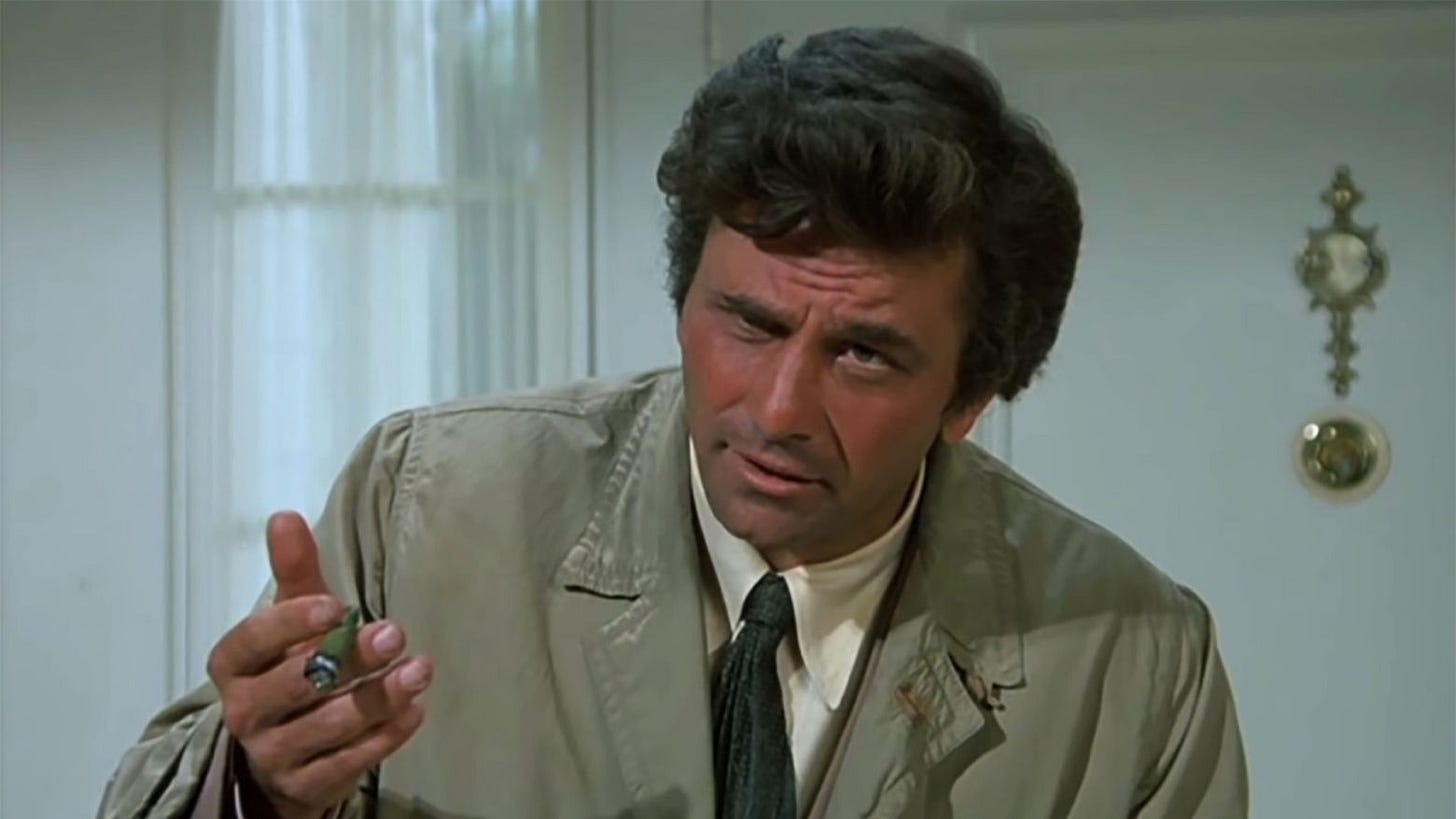

But this is at a point at which the Disco Elysium writers can hear a new chord approaching: this same openness and re-calibrating of attention to the world that the modernist novel forces on us is perfect for the detective story. Modernist novels and poetry often track the movements of a kind of flaneur who wanders about the city observing and thinking about things. Many of Baudelaire’s poems (a Decadent precursor to high modernism) capture experiences of walking around Paris and observing aging cobblestones, speculating about the dark and forbidden acts that inhabit them. Joyce’s protagonists are always just walking around the city. Bely’s Petersburg is full of loosely connecting characters pacing about different city locales while they plot, scheme and generally go insane. Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway spends much of her time walking around, thinking about things she’s seeing, remembering things. These heroes are careful perceivers and their strange disposition as attentive observers makes them ideal vehicles for the defamiliarizing techniques common to modernist novels. The stereotype of the detective (fill in your choice of Sherlock Holmes, Columbo, or Poirot here) is similarly acutely observant and can bring a strangely disinterested eye to a scene, noticing things that others don’t. Their job is to look at things carefully and reflect on them. In this sense detectives are ideal substitutes for the modernist flaneur-protagonist.

Detective stories also tend to reward the same cognitive tasks from the reader. They are about trying to piece things together for yourself, even if you’re not entirely successful. They reward distributing your attention broadly, constructing hypotheses that never quite make it to fruition, and taking in the (real or imagined) visual environment carefully. The cognitive processes of the modernist novel reader, the detective story reader, and the protagonists of the modernist period and detective genre all loosely parallel each other.6

But the chord isn’t quite filled out yet. Isometric roleplaying games often have exploration (both physical and character-based) as one of their core gameplay loops. Virtually every isometric roleplaying game has branching dialogue trees that are embedded in a variety of different characters. Virtually all of them also have hubs or open worlds that are ripe for exploration and plenty of interactable objects in areas of interest. In fact, all of these features have become a staple of roleplaying games in general. When players enter into Skyrim, they often find themselves picking through every little cave and hamlet, reading each diary entry of maddened necromancers, getting the local gossip from each tavernkeeper and cabbage farmer. Knights of the Old Republic II, like many games descended from the Bioware formula, players run through the story multiple times, picking different options so that they can maximize their influence with companions and clear out the entirety of their dialogue trees. And each time they still methodically scour the contents of each terminal and foot locker. Each time they probe the slight variations of choice. Even action-RPGs are not immune: many players of Diablo make a point of plumbing the depths of every sealed tomb they can find, greedily snatching up tattered diaries and weather logged journals that belonged to long dead adventurers.

Disco Elysium is an isometric roleplaying game, and its designers are aware of the tendencies of the genre’s players. You’re expected to click on things as much as you want, to search through every item and probe each character for interactions. The game rewards this frequently, giving beautiful descriptions, little jokes, and tight character construction. But the most obvious way it benefits the player is by giving new clues to the case that serves as the central driver to the plot. The overarching plot of many games makes this kind of open-ended exploration seem absurd. Why are you hunting for bounties when the Sith are about the conquer the Republic? Why are you helping the NCPD catch cyberpsychos when Johnny Silverhand is slowly destroying your brain day by day? Geralt doesn’t have time to look at these paintings: he needs to stop the Wild Hunt! Everything is so urgent and dawdling about and exploring each nook and cranny is narratively disorienting. But the detective framing prevents Disco Elysium from falling into this trap. It makes sense that you would stop to painstakingly search everything over when you are desperately trying to find one extra sliver of information that you missed before. It makes sense that you stop to help people with their somewhat trivial problems when you need their trust to get more info; when the Revachol Citizen’s Militia desperately needs to build some semblance of a cooperative relationship with its community.

In short: both the modernist novel and the detective story come together to give a highly perceptual story, frequently mediated by reflection on what characters have witnessed and experienced. They reward slow, methodical work with their environment, unexpected imbuing ordinary objects with new meaning and significance. Isometric roleplaying games have mechanics that are really good at rewarding these activities and making gameplay out of them. As we’ve hopefully seen, these artistic traditions fit together really well. But in the real world sociology of culture, they are on separate islands from each other. There is little overlap between those who are interested in each. One of the big strengths of the Disco Elysium crew was their ability to appreciate widely and see resonances between genres and traditions that these sociological facts made it harder to see. The result was a game that brought the best elements of each practice together.

Perhaps there is some hope for an end to the litfic-genrefic culture war here. The conflict ends not in triumph but synthesis. Genre fiction and games writers might end up following Disco Elysium’s lead (and critical success) and try to draw influence from broader swaths of literary traditions. Literary fiction writers might, just as well, try to tie their more canonical influences and avant-garde tendencies to the trends and developments that are emerging in genre fiction. Each ends up looking for ways in which their work resonates with something else; in which the strengths of each influence synergize into something newer and stronger.

But just as well, Disco Elysium may have been a stray shot in the dark. Only time will tell. The upcoming plurality of games being developed by the fractured former team will likely be the first test of the game’s staying power and influence. Until then, the devoted fans of Disco Elysium will sit with their fingers crossed, hoping that it wasn’t their only brush with some new, exciting promise of happiness.

I have Brandon Sanderson in mind here, who, by some estimates has sold over 40 million books to adoring fans all over the world.

The point of prose for these people (I’m close enough to being one of them, I suppose) isn’t to see some new world as you already see your own. Instead, one is supposed to come to see the world anew.

Robert Kurvitz is always citing Hegel and Marx as influences and so much of the world feels like a punchy mix of the sexier, moodier elements of the kind-of-gestalt-y vibes that my brain tags idealism and Marxism with.

There are so many commonalities of mood, tone and subject matter that I strongly suspect that Petersburg was an influence. The interest in the aesthetics of urban environments and the fascination with the fin-de-siecle Russian avant-garde suggested by naming a company ZA/UM also make me suspicious! The team also just cites the wikipedia page for the Russian avant-garde here: https://store.steampowered.com/news/app/632470/view/3334287173823797600.

The Thought Cabinet is one of the original innovations of Disco Elysium and one of its signatures—games industry veteran and Pentiment auteur Josh Sawyer describes at as hard to copy without ripping Disco Elysium off. Thoughts can be triggered different events and interactions in the game, causing the protagonist to mull it over, usually taking a penalty or small bonus to his skills or attributes as he thinks. Eventually the thought is completed, giving you a nifty entry that explains the conclusion that the detective has come to after reflection. The penalty or bonus shifts around a bit, usually into something a little better for you. Completing and acquiring thoughts can also yield unique interactions with other characters and skill checks.

And they parallel each other in a way that I think it reflective of the nature of aesthetic experience. I think it’s really no coincidence that the modernist novel descends from a kind of Decadent aestheticism. Bloomsbury is one obvious example.